Runaway greenhouse climate transitions

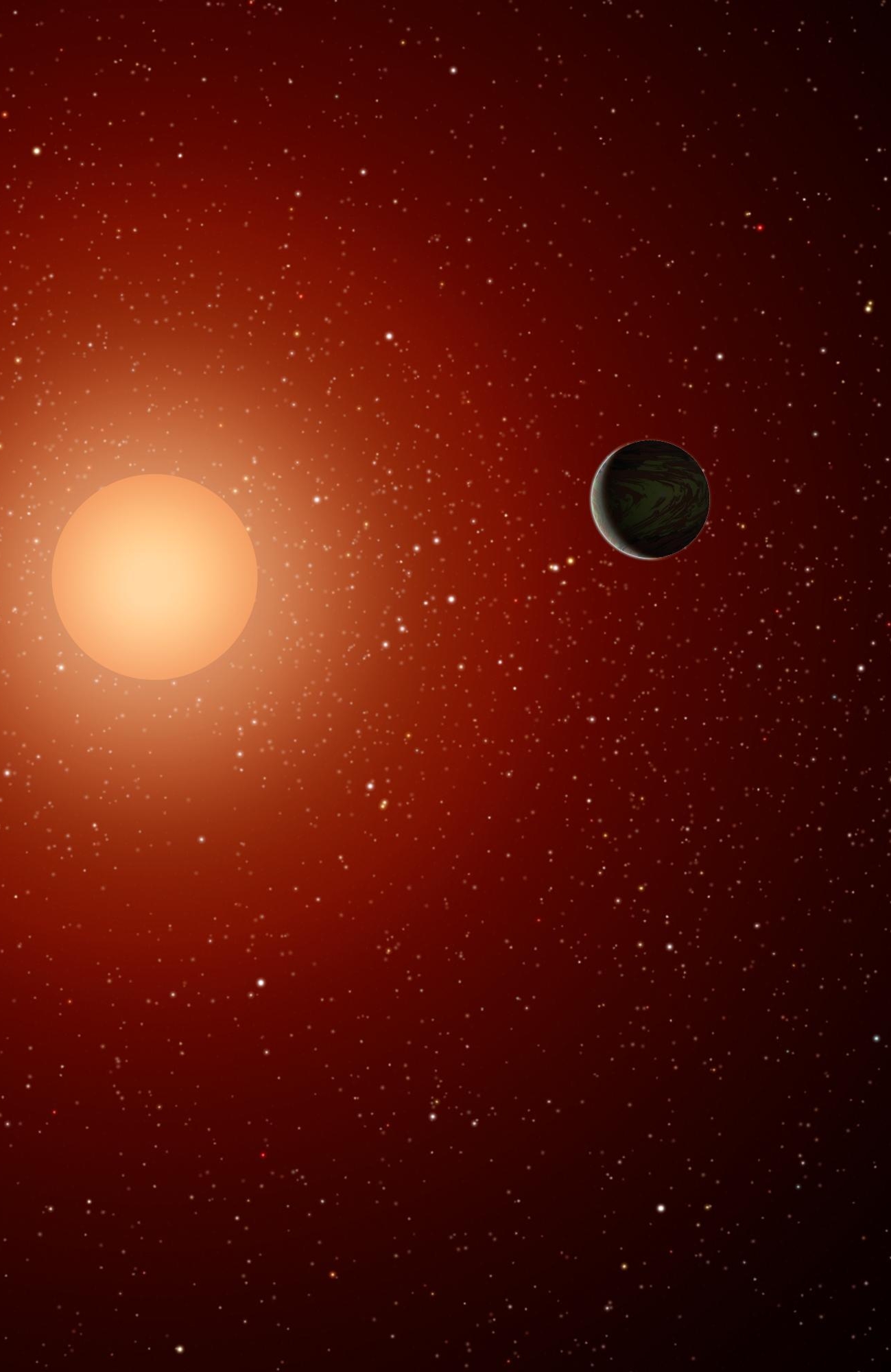

Water-rich rocky planets within the inner edge of their habitable zones are expected to undergo extreme, 'runaway' greenhouse effects that force their climate into a transient hothouse state culminating into a hot, uninhabitable, and desiccated surface. The transition from this transient runaway greenhouse effect to a post-runaway state involves many radiative and convective processes that have major implications for their present-day climate, atmospheric composition, and observable features. The habitability prospects of this post-runaway state are also dependent on factors including the initial water inventory of the planet. The more water the planet has accreted and stored in its surface reservoir, the more vulnerable its habitability will be, due to the powerful greenhouse effect of water vapor. Could a planet recondense its water vapor into surface water oceans before losing it all to space? This is an open question that depends on many factors. The question of whether the Earth is susceptible to a moist greenhouse or runaway greenhouse climate transition has also been studied; however the answer is still unclear, partly due to the same processes that make climate change on Earth difficult to predict, clouds chief among them.